Crepes are worth mastering

- Scott Daniels: We Ate Well and Cheaply

- February 9, 2018

- 1783

Disaster struck a few days ago, and my glasses were broken in a simple accident. So you’ll have to forgive this if it seems a little more squinty than usual. It makes one of my favorite parts of cooking a little more difficult: research.

Cooking is an extra delight for me as it so thoroughly combines both learning new skills with my lifelong love of history. When I make something, I want to know how such a combination of ingredients first came to be and why.

My house is completely out of shelf space, but I still have my eye on a few old cookbooks for which I’ll have to invent excuses to buy. Next on the wish list are two copies of "Larousse Gastronomique," a volume likely consulted by Julia Child as she prepared her own amazing book. For no reason I can defend, I want both the 1938 original in French and a later English translation.

Recently, believe it or not, there was a day on which the crepe was celebrated. That it was Crepe Day became obvious when many of the food-related social media accounts I follow were talking about them.

Waking up to the early alarm and checking to see what people were talking about overnight, there were all these images of crepes in any imaginable form; that’s usually a clue that something is being commemorated.

Such is our life lived in the future, as in the kinds of things we said before the turn of the century: “In the future we’ll communicate with video phones.” Little did we know how extraordinary that communication would be.

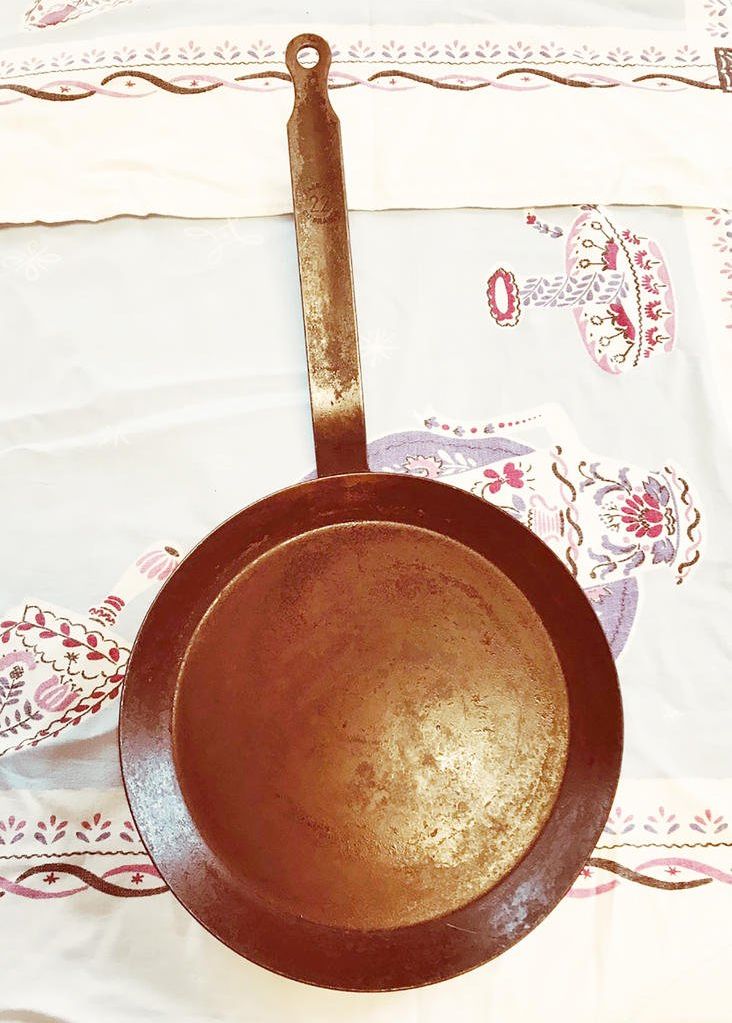

Julia Child, in "Mastering the Art of French Cooking," goes on about crepes for several pages with her usual, wonderfully detailed instructions. On her later television shows, she demonstrated making crepes using some kind of nonstick pan, which makes the process easier. But I like to use one of my favorite, prized kitchen possessions, a well-seasoned steel crepe pan, made in France.

I’ve had it long enough and have used it for everything imaginable so that it is quite blackened and free from stickiness due to the naturally built-up layers of carbon and fats resulting from repeated heating and use. It has produced far more fried eggs than crepes, but I love it all the same. It cost less than $20 when I found it many years ago.

Crepes, of course, are delicate, thin pancakes. If you want to seriously develop and master a skill set, you should spend several days experimenting with the many crepe recipes to be found out there, starting with those in the aforementioned "Mastering."

There are simple batters, yeast batters, those created for serving on their own in a sauce and those made to be stuffed. They’re versatile things and can make up the centerpiece of both desserts and entrees.

I say they are worth mastering because they aren’t as easy as they look, and you can transfer the lessons learned from your many failures to numerous other kitchen endeavors.

You have to get the heat just right. The batter must rest and chill before use. You have to be quick and learn to swirl the pan around to spread the small amount of batter. They are so delicate that you shouldn’t use a tool to flip them, so you’ll need to learn to flip them in the air or turn them with your fingers. A good cook needs asbestos fingers, and this is a good place to lose some of your fear of being burned.

Next week we’ll talk about recipes and technique.